During the month of February, the members of the Farmworker Association of Florida, low-income Latinx workers, many of them undocumented, held 5 asamblea (member assemblies) around the state to share about their lives and set priorities for action by their organization. Then delegates met in a statewide assembly. Top of their list of policy priorities is immigration reform.

By Elizabeth Henderson

When asked what impact the changes they made as a result of this project have had, a farmer wrote: “More employee buy in, less stress around Covid since people can afford to be sick.”

At the October 21, 2019 field day, the Soul Fire Farm team, Larisa Jacobson, Damaris Miller and Lytisha Wyatt, gave a tour of the farm and talked about the importance for the farm of nurturing community and staff relationships, and about how the quality of human relations reflects on relations with other beings. Larisa pointed out the value of engaging in Food Justice Certification and how it helped the farm systematize its social policies.

“Fair from Farm to Retail,” a joint project of the Agricultural Justice Project and the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA), has made its central focus to support the organic farming community in the Northeast in addressing shared social justice values while striving for dignified careers for farmers, their families, and workers on farms and to reach out to food co-ops to learn how we might support them in increasing buying from local farms and even to consider giving preference to farms with better labor practices. A central goal of AJP has been to demonstrate that even in the context of global cheap food, humane farms are possible. There are many in NOFAland! This report presents findings from this project and provides recommendations to the NOFAs on programming, training and policy.

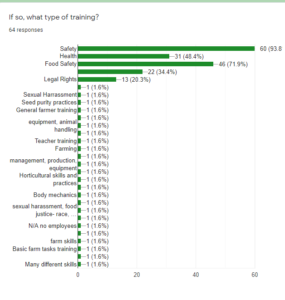

Farmers’ responses to our two surveys show that they need more support in creating written labor policies, particularly health and safety plans with training on implementing them, grievance and conflict resolution processes, mutual farmer-worker evaluations, and basic labor rights training for would-be farmers who will be working for others for anywhere from a few years to their whole careers if they become managers of farms owned by others.

This project has made clear some of the obstacles that farmers face in trying to live their social justice values through their farming. There are rigid limits to what farmers can pay themselves and their workers imposed by the cheap food policies of the US government even when there are organic premiums. We discovered that one of the most upsetting questions for farmers in our survey were questions suggesting that farmers have rights to negotiate with their buyers and to expect fair treatment. Farmers who sell into wholesale markets are resigned to their plight as “price takers” in a global market where they have little power. The best they can hope for is good working relationships with individual buyers based on maintaining high quality and adhering to the buyer’s delivery requirements.

The alternative is direct sales and many of the farmers in this project have found ways to sell directly through CSAs, farmers’ markets, on-farm markets or on-line platforms. NOFA’s 50 year “buy local organic” efforts have made major contributions to building these direct markets for farmers. Yet even here, the prevailing low prices set limits on how much farmers can charge and farmers who care about social justice do not only want to sell to customers who can afford premium prices. NOFA should seek a way to raise awareness of farmer rights and to promote those rights more forcefully in wholesale and institutional markets.

It is the moment for NOFA to be more aggressive in supporting farmer rights in the marketplace. As more and more farmers are discovering, cooperation with other farmers is the path to greater resilience, better service to customers and economic viability. NOFA can promote fair contract legislation to support farmers’ right to freedom of association so that they can negotiate together with powerful buyers. NOFA should also consider support for the Good Food Purchasing Program which encourages institutional buyers to purchase from local farms, BIPOC-led farms, and farms with fair labor practices.

We want to thank the NOFA chapters for their support and to express our particular gratitude to the farmers who made time in their busy schedules to participate in and contribute their ideas for this project.

Stage 1

In the first stage of the project, we conducted outreach through NOFA chapter newsletters and at winter conference workshops to recruit farmers to participate. Project lead Louis Battalen had one-on-one conversations with approximately 175 farmers. Liz Henderson talked with yet others. We had direct communications support via newsletters and/or google groups with such organizations as VT Young Farmers Coalition, New Connecticut Farmers Alliance, NESAWG, The Biodynamic Association, NODPA (Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Alliance), Vermont Organic Farmers, as well as the NOFA chapters. Recruitment of participants went better than expected: 84 farmers from five NOFA states completed a benchmark survey on contracts, prices, labor rights for employees, health and safety planning, child labor, wages and benefits, housing and interns, surpassing the goal of 50 farms. The farms that participated are in NY, VT, MA, CT, and NJ and range in size from a one-acre urban farm to a 2000 acre split organic-conventional vegetable farm. Based on the surveys, the project provided these farms with templates and resources to support the farmers in either strengthening or addressing their practices in these areas, going beyond what is legal to what is also fair to all involved. These materials can be found in the Agricultural Justice Project Farmer Tool-kit: http://www.agriculturaljusticeproject.org/en/info/resources-for-farms/ To evaluate the project, we are polling these farmers to find out whether the resources we provided were useful.

Based on what we have learned from the 84 farmers, we would like to make some recommendations about NOFA programming. Some of these topics are suitable as workshops, but all of these topics should be incorporated into new farmer training.

- Developing a safety plan for your farm, writing it down and training your farm team in health and safety

- Writing an employee handbook based on fair labor practices through a mutual process recognizing the needs and rights of employer and employees, including: a. Conflict resolution

b. Worker performance evaluations and how to use evaluations to encourage employees to do their best work, to identify new skills they want to master, using the evaluation process to improve your own skills as a manager, and the value of thorough files in the case of termination

c. Living wages – how to calculate living wages and how to work with employees to find a way to pay them

d. Creating a learning contract with interns to ensure that in exchange for lower wages, they are acquiring the skills and knowledge they seek - Knowing your rights as a worker – important for would-be farmers who will likely be working for others for part or even all of their farming careers.

- How to access health insurance for farmers and employees

- What is a fair contract with buyers and how to negotiate more effectively to get fair prices.

Stage 2

In 2019 – 20, the second stage of the project set out to assess the working conditions, policies and practices on the farms, identifying and highlighting the social justice values already practiced and where warranted seeking clarification and requesting additional information to ensure a quality and accurate assessment. We then provided recommendations for implementation and resources for the farms’ consideration as a way of preparing for compliance with Food Justice Certification or, if the farmer did not choose certification at this time, to address and/or strengthen specific practices. We also provided information about the processes used in an AJP certification audit and what to expect.

Seventeen of the 84 farms completed a detailed self-assessment and received personalized technical assistance and analysis of their farm’s policies. Louis Battalen and Liz Henderson reviewed the surveys, requested and then reviewed farm documents (employee handbooks or guidelines, safety plans, worker job descriptions or contracts, contracts with buyers) and then wrote reports with follow-up phone calls with a dozen of the farmers ranging from 45 minutes to two hours to discuss the reports in greater detail and answer questions. We would have preferred in-person visits to the farmers who desired one, but due to Covid-19, our visits were limited at this time to three farms in December 2020.

Originally we planned to host several field days on farms to demonstrate the Food Justice Certification process with two inspectors – a certification staff person and a trained worker organization representative who interviews the employees separately from management with full confidentiality. Before Covid-19, the project held a successful field day at Food Justice Certified Soul Fire Farm in New York. In light of the pandemic, we decided to cancel the field day component, offering, instead, a December zoom call, so Louis and Liz could meet the farmers, and the farmers could be introduced to each other—eight farms were represented on the 100 minute call; a most worthwhile and engaging exercise as it turned out! During that call, farmers exchanged advice about how to continually improve practices in working with employees. They called for streamlined templates and forms to make FJC as easy and accessible as possible with concise messaging. One farmer expressed her appreciation for the project getting her to thinkabout interpersonal relations on her farm which she finds difficult to navigate and hard to make time for. Another farmer suggested exchanging employee handbooks so farmers can learn from one another. There was impassioned talk about the need to change our culture to honor farmers and farmworkers.

A significant result is that ten of the farms have indicated that they would like to be certified to Food Justice Standards. Cali Alexander (fellow NOFA Interstate Council member, NOFA-NJ board member, and Liz Henderson’s alternate as NOFA member of the AJP board) and Liz will be providing support for these farms in the form of any additional technical assistance they need to comply with FJC standards.

Massaro Community Farm in Woodbridge, Connecticut is one of the farms that was to host a field day (“Growing a Fair Farm: what does implementing social practices look like and how to achieve and strengthen our values”). Farmer Steve Munno still intends to have the farm certified FJC and to reschedule the field day in 2021. AJP has provided technical assistance by reviewing the farm’s employment policies and practices and advising on improvements. You can read about the farm’s swift response to the pandemic, changing practices and increasing mutual aid in order to supply food to its community while keeping workers, customers and the farm family safe: http://thepryingmantis.wordpress.com/2020/06/26/massaro-community-farm-in-the-year-of-covid-19/

Explaining his decision to engage in FJC, Munno stated: “We have always grown organically, and have been certified since 2012, but it is not enough. Certified organic does not require a commitment to providing safe working conditions, just treatment and fair compensation of farm workers. The people who work here are the most important part of our farm, and in pursuing the Food Justice Certification we make our commitment clear to our staff and create a way to demonstrate our values to our customers.”

Increasing Market Pull

A second aspect of the project focused on the relationships between local food-co-ops and the farmers they buy from to enhance the market pull for farms that have good labor and training practices. We had some good conversations with General Managers, but found that produce buyers were the ones with whom we could discuss the details of this project. The buyers want to have good relationships with their farmers and are particularly keen on working with local farmers and supporting them in a variety of ways.

From the benchmark survey, we learned which farms sell through co-ops: Louis and Liz followed up through conversations on fair trade practices with 16 retail co-ops in NY, MA, VT and NH. We developed a Co-op Produce Buyer Self-Assessment Form, adapted from the Farmer Benchmark Checklist, sharing the form with a handful of buyers, and subsequently Louis reviewed the responses question by question with two of them.

Historically, food co-ops have led the way in buying from regional organic farms, but with time and market pressures, purchases from local farms have not grown to the optimum level. Three of the co-ops organized meetings between produce buyer and area growers; a first for the buyers at two of the stores. We were present at the three meetings and had the opportunity to discuss our project and present issues of mutual concern. After one such meeting, the produce manager wrote: “I really felt it was a great meeting and I appreciate you (Elizabeth) and Louis for positing the idea in the first place! Thank you.”

Farmers at that meeting were concerned about how the co-op defined local and how many miles constitutes local. They started talking about coming to an agreement on a definition that would allow the farms to band together to support one another. They came up with a list of ways the store could buy more from them and give more prominence to local farm products in display and promotion. Unfortunately, due to Covid-19, the co-op has not yet been able to implement all the good ideas, but the meeting did result in immediate orders for a few crops.

We observed that produce managers are under continual pressure to buy from major suppliers instead of from area farms. Smaller co-ops face supplier requirements for minimum orders which can effectively exclude buying from local farms. Also, co-ops are often understaffed which adds an additional incentive to take the easier path of making one big order instead of many smaller ones. Nevertheless, co-ops continue to be major buyers from regional farms. Clearly there is a lot of work that could be done to increase their purchasing and to focus promotion on buying from farms that have high standards for labor policies.

Project Outreach Louis attended the Greenfield Farmers’ Cooperative Exchange Annual Meeting, and together with Liz met with CISA (Community in Support of Agriculture), both in MA. They presented at the 2019 NESAWG (Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group) meeting in (Philadelphia) and at five NOFA chapter winter conferences, joined at these venues with farmers who participated in the project or with different farm worker organizations (CATA, Migrant Justice, & Alianza Agricola), and participated on a panel at a NOFA NH / Vital Communities Program in New Hampshire.

A VT farmer wrote: “The roundtable discussion hosted by AJP at the Winter NOFA conference was a highlight of the event. As a young farmer, I have so much to learn about the industry, including best practices. Watching older generations of farmers struggle with body/health issues and financial instability is sobering, and many of us who are just getting started can’t help but feel there must be a better way forward. The more conversations we can have around healthy, equitable farming practices, the more ideas and opportunities for collaboration will arise. More and more, people across all fields are realizing how interconnected we are. It is up to us to work together and re-structure our systems in a way that honors the health and well-being of the planet and the individuals within the system(s) while creating abundance for all.”

Data from Stage 1

The National Organic Program (NOP) chose not to incorporate social justice concerns in its standards despite many people, including the founders of AJP, advocating for it to follow the lead of international organic movements by making social justice a key tenet. A 2013 NOFA-sponsored survey of 280 farmers confirmed that many organic farmers consider social justice values an important commitment in their organic farming practices. These priorities were confirmed for the majority of the 84 farmers surveyed in this project when we asked them to rate their farming goals. The survey asked farmers to rate their priority level for their farming operation in a number of areas, on a scale of 1 to 5 (5 being the most important). Here is the choice of values-related goals from the survey:

- MAINTAINING OR IMPROVING ETHICAL TRADING RELATIONSHIPS (FAIR, HONEST, TRANSPARENT)

- PROVIDING A JUST / FAIR WORKPLACE FOR FARM WORKERS

- GETTING A PREMIUM FOR ORGANICS

- EDUCATING YOUR CUSTOMERS ABOUT YOUR FARMING METHODS

- MAKING YOUR OPERATION ECONOMICALLY VIABLE

- SHARING HEALTH & SAFETY ISSUES WITH YOUR EMPLOYEES

- PAYING YOURSELF A LIVING WAGE

- PAYING YOUR EMPLOYEES A LIVING WAGE

All of the farmers who took the time to fill out the initial survey rated elements of fairness as their top priorities. Interesting to note that the lowest scores went to things that give an economic advantage to the farmer her/himself:

85% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to maintaining or improving ethical trading relationships;

89% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to providing a just / fair workplace for your workers:

66% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to getting a premium for organics

75% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to educating customers about farming methods

86% gave a rating of 4 o 5 to making your operation economically viable

76% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to sharing health & safety issues with employees;

60% gave a rating of 4 or 5 to paying yourself a living wage

81% gave a rating of 5 to paying employees a living wage.

Data collected from the 84 farms:

- 22 farms on 100 acres or more, 14 farms on five or fewer acres;

- Although predominantly vegetable, 21 listed poultry/dairy as the major commodity, and seven listed fruit;

- 26 have been farming for 20 or more years, 9 have been farming for fewer than five;

- 50 are certified organic;

- 27 earn additional income through off-farm employment;

- 35 have year-round paid employees;

- 20 farms have more than 10 employees (10 have 10-20; six have 20 – 40; and three over 40);

- 20 farms hire apprentices or interns;

- 22 pay family members;

- 42 sell at least 50% or more directly to consumers and 19 have some sales to food co-ops.

- 62 requested a copy of AJP’s Employee Manual Template;

- 53 are interested in receiving free technical assistance;

- 38 are willing to receive on-site assistance;

- 60 would attend a workshop.

Summary of responses from the Stage 2 Checklist:

- 9 of 17 said price covers costs of production

- All 17 are willing to respect right to association

- 9 have developed and communicated conflict resolution process

- 11 have some type of written agreement with workers

- 4 train workers in legal rights

- 15 said that they do not terminate without just cause

- 9 said workers have right to appeal disciplinary action

- 12 have health and safety plan

- Fewer provide training on Worker Protection Standards

- 12 say they pay a living wage

Funding for this project came from the New Visions Foundation, Clif Bar and the Rupp Family Foundation.

Working together, the Agricultural Justice Project (AJP) and NOFA—one of AJP’s four founding members—are launching a project to support the organic farming community in addressing our shared social justice values while striving for dignified living careers for farmers, our families, & the workers on our farms.

Support our mutual efforts toward achieving a fair and equitable food system by completing this brief checklist of your own current practices.

An introduction with details on our Project is included with our Farmer Benchmark Checklist—we expect the Checklist should take only 15 minutes to complete. We based it on AJP’s high bar Food Justice Certification Standards. As you can read in our introduction, technical assistance in support of the various topics is available. Both AJP & NOFA are committed to providing the technical assistance farmers request either through the AJP tool-kit resources and / or through workshops & presentations on specific issues requested by farmers who want to improve labor policies and practices and who want fair, equitable, transparent agreements & pricing. Specific areas covered include achieving a living wage for farmers and farm workers alike, health and safety, conflict resolution, apprentices, and developing a premium in the marketplace.

This support will be gratis, with no obligation to engage in AJP’s Food Justice Certification.

Thanks for participating—Louis Battalen & Elizabeth Henderson, NOFA Domestic Fair Trade Committee & the AJP

From the Northeast Organic Farming Association Interstate Council

November 20, 2018

Over the past two years, NOFA members have observed with indignation the series of arrests in Vermont and New York of dairy farmworkers who have the courage to take action to improve working and living conditions on farms in these states. NOFA stands in solidarity with Migrant Justice in taking peaceful, legal actions that should be protected by the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

The American Civil Liberties Union in Vermont, the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, the National Center for Law and Economic Justice and the National Immigration Law Center have filed a federal lawsuit claiming that immigration agents are targeting undocumented organizers for their activism in Vermont. The suit accuses Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security and the Vermont Department of Motor Vehicles of carrying out a multiyear campaign of political retaliation against members of the group Migrant Justice. According to the lawsuit, Migrant Justice was infiltrated by an informant, and its members were repeatedly subjected to electronic surveillance. At least 20 active members of Migrant Justice have been arrested and detained by ICE. The lawsuit seeks an injunction, asking a judge to put an end to ICE’s targeted campaign of retaliation against Migrant Justice and its membership.

Enrique Balcazar, a former dairy farmworker who became an organizer with Migrant Justice, has been a speaker at several NOFA conferences. In filing the suit he stated: “But as we stand up and fight for our rights, we are hunted down and targeted by ICE. And that’s why we are here today, to stand up for our rights and file this lawsuit against ICE and the Vermont Department of Motor Vehicles. In the past two years alone, there have been over 40 community members associated with Migrant Justice who have been arrested by federal immigration authorities. Many of them have since been deported. And in nine of these cases, we have clear evidence that these arrests were retaliatory, targeting people because of their involvement in Migrant Justice. ICE has been persecuting us. They’ve been surveilling Migrant Justice and its membership, with the objective to repress our voice, to keep us quiet, to stop us from organizing for our rights and to take retaliation against us for the way that we express ourselves and when we expose their abuses of power.”

Background on Migrant Justice

Migrant Justice was key to passing a law in Vermont in 2013 allowing for the creation of the driver’s privilege card, a driver’s license available to anybody regardless of immigration status. Most immigrant farm workers in Vermont live in isolation on rural farms with no access to public transportation, and many were spending years at a time on those farms without the freedom to go anywhere because of lack of access to transportation.

In October of 2017, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream signed an agreement with Migrant Justice, becoming the first dairy company to join Migrant Justice’s Milk with Dignity program, a binding commitment that requires their suppliers to uphold a farmworker-authored code of conduct, guaranteeing rights and wages, housing, health and safety, scheduling, and to be able to organize free from retaliation and discrimination. So far, 300 dairy farmworkers on 72 farms are covered under this program. Ben & Jerry’s pays a premium to the farms in order to redistribute profits down the supply chain enabling the farmers to make improvements and pay increased wages to their employees.